I kissed him gently on the forehead, looked into his vacant blue eyes and said “Goodbye, Papa. I love you.”

I’ve no idea whether he heard me or not.

That was the last time I saw my father alive. He was pumped full of morphine to ease his passing.

Rewind 5 days:

It’s the end of May 2017, and I have just flown in from Manchester, UK to be with my father at the Helios Klinikum in Schleswig, Germany.

The doctor I had spoken to the day before had urged me to be at my father’s bedside. “It’s not looking good. The second round of antibiotics hasn’t worked,” he had said.

My father had contracted bacterial pneumonia nine days earlier, a common occurrence with Alzheimer sufferers. Food that accidentally gets into the windpipe develops harmful bacteria, as it isn’t cleared through coughing. Alzheimer sufferers lose their normal reflexes in the late stages of the disease.

My sister had flown in from the US the previous day, and as soon as I arrived, the two of us, and our mum were bustled into a family room with sterile white walls and green chairs.

“I understand your husband has got a living will which gives you overall authority over his care.” The doctor looked at my mum. “I believe it is time that we discuss what care should be considered from now on.” He pointedly looked at each of us in turn.

What he had meant but wasn’t allowed to say was the dreaded ‘P-word’: palliative care.

I can only describe the emotions I felt at that moment as heart-crushing inner chaos of grief, uncertainty and guilt.

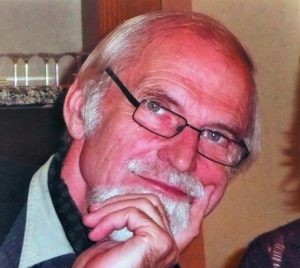

Here, the three of us were expected to decide the fate of the man who’d always been such a force of nature, whom we still saw as the head of our family, despite having lost the essence of him many years ago to his progressive 11-year illness.

We had, of course, discussed this subject with great composure several times in the last few years. Easily done from a sometime-in-the-future distance. Being faced with the harsh reality now was a totally different matter.

The doctor left us, and we looked at each other. “Papa wouldn’t have wanted this,” my mum said. “He would have wanted to go.”

We nodded. Yes. He wouldn’t have wanted to prolong his and our suffering with continuing medical intervention that, the doctor had assured us, would have left him at best in a vegetative, intravenously fed state in a care home.

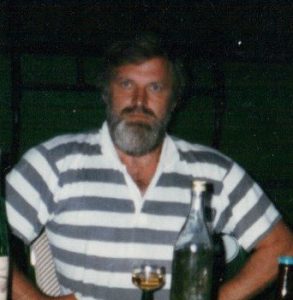

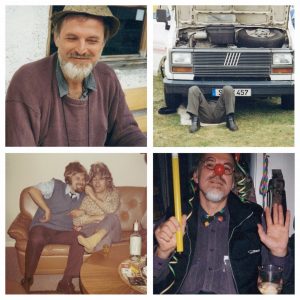

Our Papa had always been so strong, the ultimate party animal, loving life and fun above all.

“Now, let’s have some fun,” had been his words to whoever had approached his hospital bed before pneumonia had reduced him to a mostly semi-conscious, gravely ill shell of a man.

No. He wouldn’t have wanted this.

The next day, we had a visit from the Palliative Consultant. “His passing will be made painless with regular morphine injections and mucus clearing treatments,” she assured us. “He won’t suffer.”

We did feel so sure then that we had made the right decision.

Nothing, however, could have prepared us for the agony that lay ahead in the next few days, the torture that comes with dying from pneumonia.

My own feeling of guilt on witnessing how the disease progressively claimed my father’s body was so intense that at times I felt physical pain.

The three of us hardly talked during these few days, we just watched and waited. Praying that he would be released soon.

I only managed to get through the ordeal by desperately clinging to the hope that it was our agony alone, that my dad really didn’t feel any of it.

I had doubts, of course. And they were overpowering.

I had the urge to stand up and scream, “Enough! I’ve changed my mind. Treat him with whatever, just make it stop!”

But I didn’t. I suffered in silence because I knew it was the right thing to do.

Today, almost 17 months later, I’m finally able to talk about the decision to let my dad go.

I have finally accepted that there is no wrong or right in a situation like this. You have to go with your instinct, commit to and accept the choice you have made.

It has taken me a long time, but I no longer wake up every morning with the picture of our final goodbye in my head and the sick feeling of dread in my stomach.

I can now start to enjoy the happy memories of his whole life rather than suffer from the effects of the mental images from his last few days in the hospital.

“What is embedded deep within your heart, cannot be taken away by death.” Johann Wolfgang Goethe

R.I.P. Karl Dieter Launus 17.6.1941 – 30.5.2017 ❣️

Author’s comment:

Please feel free to share your thoughts about this post by commenting below.

Do you have an inspirational story to tell? Why not take a look at our Contributor Page and get in touch!

Thank you,

Caren

Caren is a qualified and experienced digital copy & content writer with both a corporate and small business owner background. She runs KreativeInc Agency, a web design, development and content creation agency with her autistic son Callum Gamble.

She specialises in creating Inbound Marketing content for business websites and blogs. Using her expert knowledge, skills and personal experience in business development, personal improvement and autism, she crafts content that makes people take action. Her work is found in retail publications, professional websites, on her writer’s platform StoryBlog and more.

She is also an active advocate of neurodiversity in the workplace and co-founder of the NeuroPool network, neuropool.co.uk. Here, she is organising free educational workshops for employers on how to utilise the extraordinary talent found in people with autism, ADHD, dyspraxia and dyslexia within their business.

When she isn’t typing away on her keyboard or spreading her mission, you can see her having her nose buried in a book or hiking up and down the steep hills of the Yorkshire countryside with her husband, son and daughter.

More information at

An awful situation sometimes calls for brave but painful decisions, which are ultimately the right decisions. I’m sure many people can relate to what you went through and perhaps it helps them in the decisions they had to make.

Thank you 💚

The way you talk of your father shows the love and respect you have for him and the decision your family made marked that completely – absolutely beautifully written and heartfelt ❤️

Thank you so much for your lovely words, Jane ❤️

Oh Caren, I know the depth of your love for your dear Papa and I can only imagine the difficulties of the long goodbye that you all went through. But the fact that you emerged from the experience and now can write about that time in a most tender and loving way is a testament to your upbringing and the strength given you by Karl-Dieter. He is very proud of you.

Thank you for these lovely words, Paul ❤️